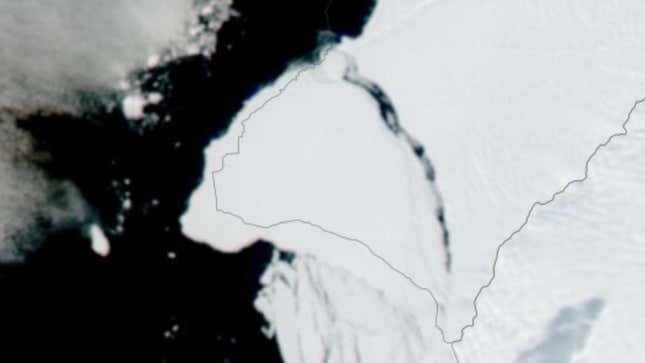

Crash diet alert: Antarctica’s Brunt Ice Shelf has slimmed down by about 256 billion tons. As part of a major calving event, an iceberg nearly the size of Houston, Texas, separated from the continent on Sunday, according to the British Antarctic Survey.

It’s the second major iceberg break for the Brunt shelf in recent years. A previous one in February 2021 was, at the time, the largest known Brunt calving since satellite data collection began in the 1970s. That 2021 iceberg, named A-74, was about 470 square miles (1,270 square kilometers) in area. But this week’s has surpassed it, with an iceberg 492 feet (150 m) thick and more than 598 square miles (1,550 square km) across, Dominic Hodgson, a glaciologist with the British Antarctic Survey, told Gizmodo in an email.

The two iceberg formations are part of the same, ongoing calving event, and Hodgson added that “together, they represent a substantial reconfiguration of the ice shelf (and the coastline of Antarctica).”

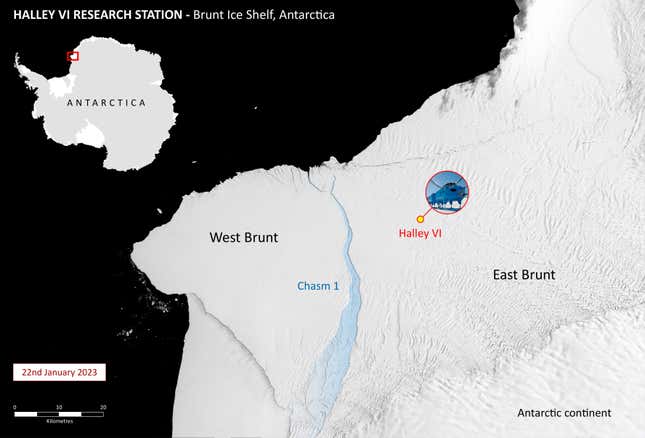

The Brunt Ice Shelf is located east of the frozen continent’s Transantarctic Mountain range. It’s home to the United Kingdom’s Halley VI Research Station and is one of the most closely monitored ice shelves on Earth. It’s one of the approximately 300 ice shelves along Antarctica’s perimeter, covering about three quarters of its coastline.

This week’s breakaway berg is the largest known for Brunt, but not for the continent overall. That honor goes to A-76, which tore away from the Ronne Ice Shelf in May 2021 and had a surface area of 1,668 square miles.

Antarctic researchers have known for years that a large Brunt calving event was likely at this site. Chasm-1, which became the breaking point, had been active and growing for more than a decade, according to the BAS press statement. And since then, iceberg formation has been a question of when, not if. In 2016, BAS even moved the modular Halley VI more than 14 miles (23 km) inland to avoid the possibility of the research station floating away.

Now that this most recent break is final, scientists expect the newly formed iceberg to follow in the flow-steps of its A-74 predecessor and move along with the Antarctic Coastal Current. BAS will continue to track the as-of-yet unnamed berg.

While the thought of a massive ice chunk larger than most U.S. cities floating off into the Weddell Sea might seem alarming, Hodgson and his research colleagues were careful to note that calving is a normal Antarctic process. Moreover, there’s no evidence that human-caused climate change contributed to this particular iceberg formation.

Antarctica’s land mass is almost entirely covered in an ice sheet that continually flows outward toward the coast from the center. In areas where the coastline is protected enough, that glacial flow forms ice shelves that float atop the ocean but remain attached to the continent. Ice is constantly being pushed out from Antarctica’s center, and so ice shelves are continually in flux. Brunt flows westward at a rate of about 1.24 miles (2 km) each year. “Unsupported by land, eventually the ice shelf weakens to the point where it breaks into icebergs,” explained Hodgson.

Ice shelves are vulnerable to melting from the surrounding air and water temperatures, but Hodgson explained that “atmospheric temperatures over the Brunt Ice Shelf are consistently below freezing, and no warm ocean water currently penetrates into the cavity under the ice shelf.”

However, the same can’t be said elsewhere in Antarctica. On the other side of the Transantarctic Mountains, in West Antarctica, research has demonstrated that the continent is rapidly losing ice, largely due to ocean warming. In total, the continent incurred a net loss of 3 trillion tons of ice between 1992 and 2017, according to one 2018 study. And “this ice loss is expected to accelerate in the future,” Hodgson said.

The Brunt Ice Shelf may not be bearing the brunt of climate change, but Antarctica as a whole is still feeling the effects. Though it’s not a signal of broader warming, an iceberg the size of Houston yeeting itself into the ocean is still a sight to behold. More satellite images are likely to surface in the coming days, but click through to see what scientists have captured so far.