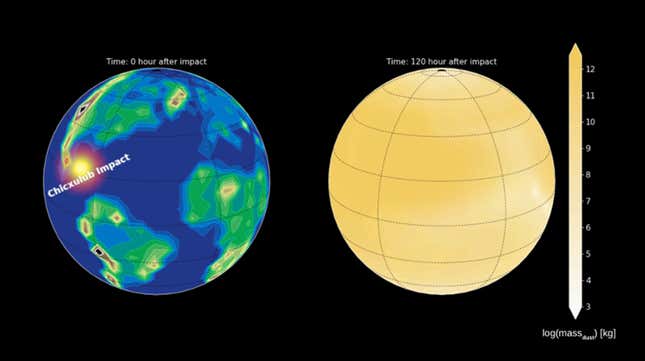

We all know how the story goes: a large asteroid falls to Earth from space, slamming into the Yucatán Peninsula with 100 million megatons of force. The impact spawned tsunami waves best measured in miles and kicked up dust, soot, and sulfur that blotted out the Sun, causing the death of about 75% of Earth’s species, including all dinosaurs but the ancestors of birds.

Now, a team of scientists posit that silicate dust played a larger role in the mass extinction than previously estimated. Using paleoclimate simulations and details of the material kicked up by the impact, the researchers determined that fine dust may have stayed in Earth’s atmosphere for up to 15 years following the asteroid impact, which could have cooled the Earth significantly—by about 27°F (15°C). The team’s research was published this week in Nature Geoscience.

Different ideas about what exactly killed the dinosaurs—and plenty of other organisms 66 million years ago—have been suggested over the years. But something blocking out the Sun, whether it be volcanic activity or fallout from an asteroid impact, is frequently in the cards. In 2020, a different team of researchers posited that wildfire soot, caused by the impact, triggered the mass extinction. And in 2021, another group found that dinosaurs were already in trouble before a big rock slammed into what is now Mexico.

The researchers ran simulations which “support a dust-induced photosynthetic shut-down for almost 2 [years] post-impact,” the team stated in the paper. “We suggest that, together with additional cooling contributions from soot and sulfur, this is consistent with the catastrophic collapse of primary productivity in the aftermath of the Chicxulub impact.”

Without most plant life doing photosynthesis—the process by which they convert sunlight into chemical energy—plants would have died wholesale, causing a domino effect up the food chain. For about 620 days (1.7 years) after the impact, the planet would have been plunged into a cool, dark wasteland, according to the new research. Flora and fauna that could enter a dormant stage and weren’t picky about their food sources were more likely to get through the period alive.

The Chicxulub impact was so intense it left 50-foot ripples on the seafloor and caused debris to rain down as far north as North Dakota—which is where the recent team collected fine-grained material from the impact for sampling. The site is called Tanis, and is famous for being rich with fossilized creatures that died in the immediate fallout of the asteroid impact. Data previously taken from Tanis revealed that the event happened in springtime, 65 million years ago.

“We specifically sampled the uppermost millimeter-thin interval of the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary layer,” said Pim Kaskes, a geochemist at Vrije University Brussel in Belgium and co-author of the study, in a Royal Observatory of Belgium release. “This interval revealed a very fine and uniform grain-size distribution, which we interpret to represent the final atmospheric fall-out of ultrafine dust related to the Chicxulub impact event. The new results show much finer grain-size values than previously used in climate models and this aspect had important consequences for our climate reconstructions.”

The researchers stated that more studies of the K-Pg boundary—the geological layer that includes the fallout of the Chicxulub impact—would help clarify exactly how life rebounded in the months and years after the event.

More: Dinosaurs Were Already in Big Trouble Before the Asteroid, More Evidence Suggests