In 2005, the residents of Ban Si Lam, a village in northeastern Thailand, dug out their local pond. Amid the topsoil they found some pottery, ceramics, and—to their surprise—an alligator skull.

Researchers initially identified the skull as that of Alligator sinensis, the critically endangered Chinese alligator. But today, a different team of researchers posit that the skull is around 200,000 years old and belongs to an extinct species of alligator. The team’s research was published in Scientific Reports.

“The dispersal of Alligator from North America to Asia represents one of the major enigmas in crocodylian evolution,” said Gustavo Darlim, a researcher at Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen and the study’s lead author, in an email to Gizmodo.

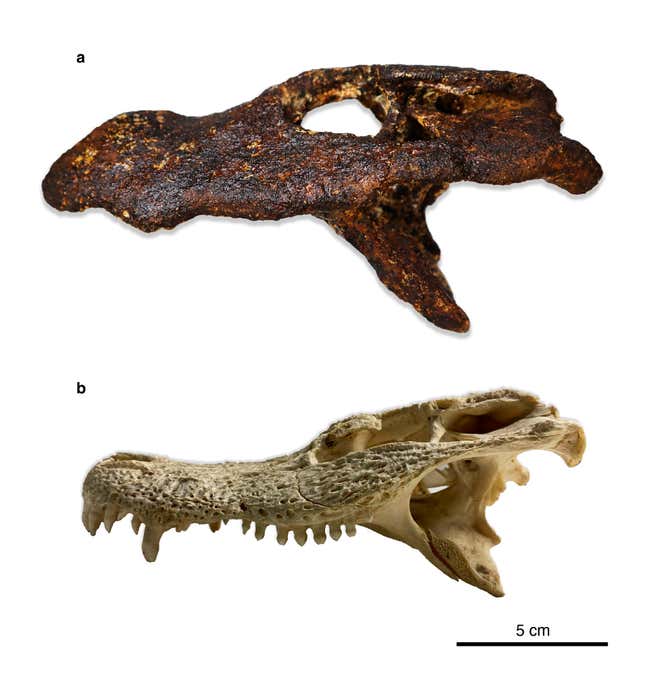

Darlim’s team dubbed the new species A. munensis, named for the Mun River which flows near the site. The skull was dated to younger than 230,000 years ago, and had some features that set it apart from modern alligator species: the reptile had a short, broad snout, a tall skull, and fewer teeth than its extant relatives. With a skull roughly 9 inches (25 centimeters) in length, A. munensis could hardly be called a giant.

In the research, the team—including researchers from Tübingen, Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University and Thailand’s Department of Mineral Resources—studied the skull’s morphology and compared the new species’ relationship with other extinct alligators, as well as the extant American alligator (A. mississippiensis), Chinese alligator, and spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus).

Based on their evidence, Darlim said, “A. munensis does not represent an ancestral form of the Chinese alligator, but a species from a different lineage that was split up from the Chinese alligator in the past.”

Based on the shape of the animals’ skulls and their tooth morphology, the researchers propose that A. munensis had the ability to crush prey, perhaps shellfish or snails. However, they don’t know what amount of the animal’s diet was constituted by hard-shelled prey—merely that the alligator could handle them.

The Chinese alligator and the newly described species share some morphological similarities, including a ridge at the top of both animals’ skulls. The team posits that the two species are more closely related than the American alligator, and the former two may have shared a common ancestor in one of the river systems of southeastern Asia.

Furthermore, the researchers suggest that geological changes in the Tibetan Plateau may have caused the eventual independent evolution of the two species.

“One of the more intriguing questions is to know when was more precisely the time of the split between A. munensis and A. sinensis,” Darlim said. “We are currently working on developing this analysis that would help us to better understand not only how Alligator got to Asia, but also the dispersal of Alligator within Asia.”

The Chinese alligator remains critically endangered, and is threatened by habitat loss and food resource contamination by human fertilizers and pesticides, according to the Wildlife Conservation Society. Without more aggressive conservation measures, the reptile may go the same way as its Pleistocene relative.

More: New Research Indicates Endangered Species Act Is Toothless