Meta says it has identified and removed more than 7,700 shady accounts and 990 pages on Facebook linked to Chinese law enforcement in what the company is calling the “largest known cross-platform covert influence operation in the world.” The accounts, which tended to boost positive commentary about Chinese policies and negative posts about the US, were also active on Twitter, Reddit, TikTok, Medium, Soundcloud and more than 50 other online platforms and forums, according to Meta’s Q2 Adversarial Threat Report. Researchers linked the massive network of accounts to another pro-China online operation dating back to 2019, which security researchers call “Spamouflage.”

“Taken together, we assess Spamouflage to be the largest known cross-platform covert influence operation to date,” Meta said.

Meta says it traced the influence operations to a geographically dispersed collection of accounts in China that appear to have received content direction from a singular central source. That content mostly consisted of spammy links, political memes, and text posts, all with the apparent intent of boosting China’s image—particularly in the Xinjiang province—and criticizing Western foreign policy. Xinjiang is the primary region where human rights organizations have accused Chinese authorities of persecuting the country’s Uyghur Muslim minority.

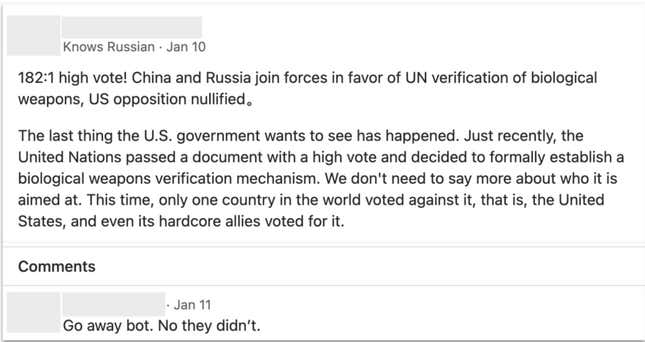

The posts varied in content and quality, with many containing typos and others bordering on incoherent. Several repeated headlines noted by Meta show the pro-China accounts attempting to question the origin of the Covid-19 pandemic, with some even suggesting the US may have been the real culprit.

“The truth is: Fort Detrick is the place where the COVID-19 originated,” one of the translated posts reads. Fort Detrick refers to a US military base in Maryland. Another post translated into eight different languages attempted to link the outbreak to “suspicious” US seafood shipments.

“Great clue! Suspicious U.S. seafood received before the outbreak at Huanan Seafood Market,” one translated post read.

The posts similarly targeted former Donald Trump ally Steve Bannon as well as prominent Chinese virologist Yan Limeng and New Yorker journalist Jiayang Fan. One headline referred to Fan as the “‘stirrer’ with a distorted mindset.”

In total, the 954 pages China-linked pages identified by Meta managed to attract around 560,00 followers. Operators involved in the operation spent just $3,500 on Facebook ads, which they paid for primarily in Chinese yuan, Hong Kong dollars, and US dollars. Despite its sheer size, the influence operation doesn’t really seem to have picked up much momentum. Meta, in its report, says the accounts “struggled to reach beyond its own (fake) echo chamber.” Most of those accounts, Meta says, were detected and removed quickly by Meta’s automated systems. The company believes those actors, foiled on Facebook and Instagram, may have then tried to again on smaller platforms.

“It is important to keep reporting and taking action against these attempts while realizing that its overall ability to reach authentic audiences has been consistently very low,” Meta said in its threat report.

The accounts weren’t great at hiding their tracks either. Many of the posts identified tried to use terms like “I” or “we” to appear more personal and convincing, but they went on to copy those same supposedly personal posts across hundreds of different accounts on multiple platforms. In some cases, Meta says it identified posts with what looks like a serial number, suggesting multiple accounts may have been instructed to simply copy and paste content from a numbered list.

Spamoflague, as Meta calls the operation, is unique for its sheer size and penetration of the web. Aside from the now somewhat predictable spam posters on Facebook, the operation also consisted of accounts sharing audio of pro-China propaganda on Soundcloud and hundreds of cartoons posted to Pinterest and Pixiv. Chinese-linked accounts even authored posts on the question-and-answer forum Quora, at times sending explicitly pro-China replies to posts that had nothing to do with the country or politics. Accounts typically posted between 5-10 times per day. From what Gizmodo can tell, this truly was a “throw it against the wall and see what sticks” variety of online influence.

The cheap accessibility and potential for overwhelming reach afforded by internet platforms have made them an obvious avenue for intelligence agencies and government operators interested in trying to subtly shift narratives. But these operations aren’t just limited to the usual suspects in China and Russia. Just last year, researchers at Meta and Twitter discovered at least 39 Facebook profiles and nearly 300,000 tweets linked to a “covert, pro-U.S. influence operation,” intent on spreading pro-US narratives in Russia, China, and Iran.