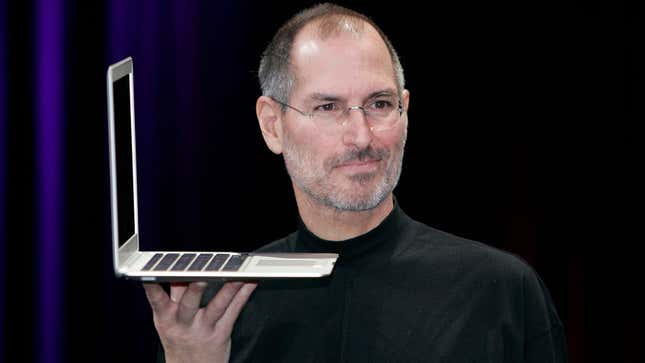

When Apple launched the MacBook Air at the end of January 2008, it was an overpriced marvel of design and tech. The laptop, a silvery sliver of machined aluminum, was .76 inches at its thickest and weighed less than three pounds. In an impractical but effective on-stage demonstration, Steve Jobs unveiled the the $1,800 computer by removing it from manila interoffice envelope to demonstrate just how svelte it really was. “What is the MacBook Air?” he asked while pacing the stage. “In a sentence, it’s the world’s thinnest notebook.”

Ten years later, the market is flooded with slim laptops, and while Apple has kept the Air on shelves, it let its guts languish as it shifted focus to other, more profitable products. In the decade since the company first released the Air, it’s made a handful of faster, slimmer, and more powerful laptops. But despite all of this, none have changed the trajectory of mobile computing quite as much as the Air.

When Apple released the original MacBook Air, the reception was divided. Some thought it was a waste of money; others believed it was a vision of the future. “The Air showed the possibilities of what computing could be,” Francois Nguyen, creative director at the design consultancy Frog, tells Gizmodo. For industrial designers like Nguyen, the MacBook Air signaled a significant shift in how they did their job. It changed they way they thought about manufacturing; it emboldened companies to invest in good design; and in the process, it elevated what consumers demanded of a laptop.

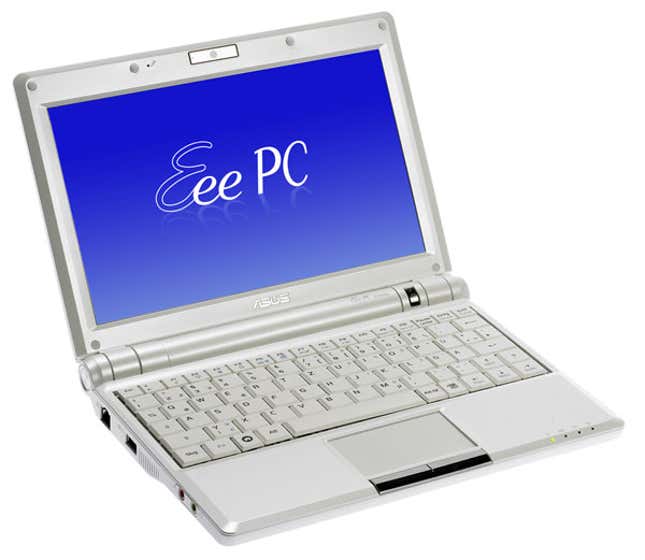

Cheap netbooks like the Asus Eee PC 900 were what most people thought ultraportables would look like in 2008. The MacBook Air was born at an interesting time. In 2008, mobile computing was stuck in two worlds: bulky, high-powered workhorses like the Lenovo ThinkPad that were technically portable, but a pain to carry around, and chintzy, lightweight plastic netbooks like Asus’s line of Eee PCs that could do little more than connect to the internet and run simple software. The Air fell somewhere between the two. Apple worked with Intel to miniaturize its Core 2 Duo processor chip, the same processor used in its more powerful MacBook and iMac, reducing the size by 60 percent. This smaller chip design enabled the Air to shrink its logic board, making more room for batteries and reducing the size of the computer altogether.

Originally, Apple built the Air to compete with lightweight portable computers like Sony’s TZ notebooks, which featured a similar tapered design and 3-pound weight. During his January 2008 presentation, Jobs pulled up a graphic comparing the TZ’s thickness to the Air’s. “The thickest part of the MacBook Air is still thinner than the thinnest part of the TZ series,” he gloated. “We’re talking thin here.”

Indeed, the Air was a remarkable feat of industrial design. “You had these razor sharp edges,” Nguyen says. “It doesn’t have any give to it; it’s just this beautiful, solid object.” Apple’s use of quality materials gave the notebook a pleasurable heft. Its full-sized keyboard is, to this day, one of the best Apple has ever designed. The Air’s form was so iconic that in 2012 Apple was awarded a patent to protect its wedge silhouette from competitors who had begun to copy it.

It wasn’t a perfect computer, though. The original Air had limited storage and no internal optical drive—the latter was more or less the equivalent of removing the headphone jack from an iPhone today. Its single USB port was a prescient glimpse of what was to come, but it was impractical and unheard of at the time. Apple attempted to make up for those perceived shortcomings with its sleek unibody design and multi-touch trackpad. Still for many people, the Air was simply a very pretty, very expensive netbook. “By definition, the Air really was more or less a netbook,” Nguyen says. “But it was too damn beautiful to be lumped in with all these other low-cost plastic offerings that were coming out.”

It’s true that Apple stripped the Air of certain technologies that consumers had grown used to, but for some, the Air’s lack of features was a benefit. “Apple took a stance on discipline and reductionism,” says Mladen Barbaric, who founded the industrial design studio Instrumments as well the branding and product design firm Pearl Studios. “If you’re going to make the ultimate travel laptop, you’re going to have to make some tradeoffs.” In retrospect, those tradeoffs, however painful they were at the time, ushered in the untethered way of working that’s so common today.

When the Air first launched, the cloud was still an imperfect and nebulous concept. I remember repeatedly deleting files from my laptop when its hard drive inevitably reached capacity. But Apple took an early bet that enough people prized portability over power, and it eventually paid off. “It forced me to modernize my way of working,” says Barbaric. “I still work this way today.”

The short-term headaches that the Air induced were worth it for early adopters like Nguyen, who believes the Air turned working into a luxury activity. Nguyen recalls owning the Air as the ultimate workplace status symbol. It was a way to distinguish between the worker bees, who needed heavy-duty computers to do the actual grind of designing, and the bosses, who could slip the Air out of their bag and shoot off a few emails. “My goal is to get to the point where I have to carry nothing,” he says.

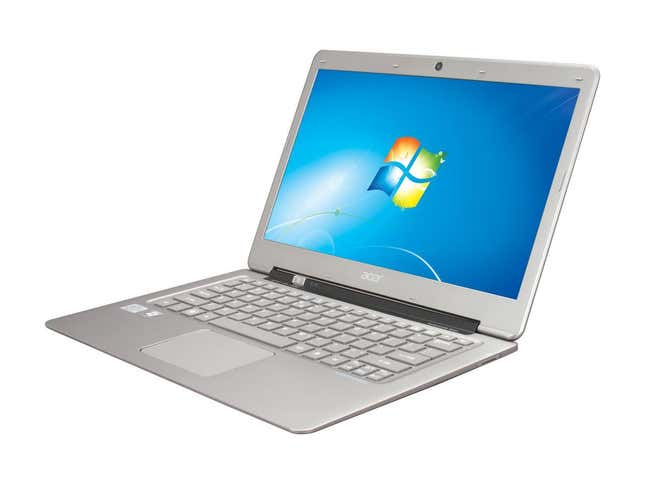

By 2011 Apple had introduced a smaller 11-inch Air that started at $999, and reduced the price of the base 13-inch model to a much more reasonable $1,299 to compete with companies like Acer, Asus, and Lenovo who with the help of Intel’s miraculously shrinking guts, were getting ready to produce skinny, powerful machines of their own. These PC “ultrabooks,” which after trickling out at the end of 2011 and had their big coming out party at CES in 2012, were positioned as a less-expensive Windows-based alternative to the Air.

Today, capable, lightweight notebooks are the norm, and it’s not a stretch to thank Apple for that. “They created a new market around what’s considered an ultra-portable laptop,” says Barbaric.

Apple was able to do that by establishing new manufacturing processes that helped streamline the production of its clean-lined metal gadgets. In 2008, CNC milling, the process by which the Air is made, was primary used for making prototypes and low volume production. Milling was expensive; it required special tooling that could precisely whittle a block of aluminum down to the super-sharp edges found on the Air. Over the course of years, Apple invested in the process and scaled it up with the intent to incorporate unibody aluminum design in more products than just the Air. Other consumer electronics companies took notice and starting thinking about how they could do the same. “I can tell you that the interest in super-thin laptops spiked immediately after the launch of the MacBook Air,” Barbaric says. “It impacted people right away, but because development takes a while, you didn’t see that immediately on the market. You saw the ripple effect over time as people worked through this behind closed doors.”

To this day, Apple still uses the processes it put in place for the MacBook Air to manufacture MacBooks and MacBook Pros. The forms are different, but the DNA is the same. Apple figured out how to shove miniaturized components into an ever-shrinking metal body without relying on the the Air’s tapered visual effect, which gives the new MacBook a different silhouette. The primary virtues of the new MacBook—its thinness and lightness—are evolutionary traits inherited from the very first Air. “They could’ve named the new MacBook ‘MacBook Air and you probably wouldn’t have blinked,” Barbaric says.

Instead, Apple decided to let the Air stand alone and die a slow, laborious death. Just last week, the company dropped a hint that it might finally kill the Air after years of letting it lag. It’s hard to deny that the time has come for the Air, at least in its current form, to cede its place as Apple’s entry-level notebook. But it’s just as important to remember its legacy as the spiritual precursors to the laptops we know and love today.