“Have you met Jacob?” It’s the first question they ask me, inside a small meeting room, deep in the heart of Facebook’s Menlo Park campus, where keyboard fans from across the Bay Area have braved the rain to show off their boutique builds. Many of them have spent thousands of dollars on their board collections, with custom switches and keycaps.

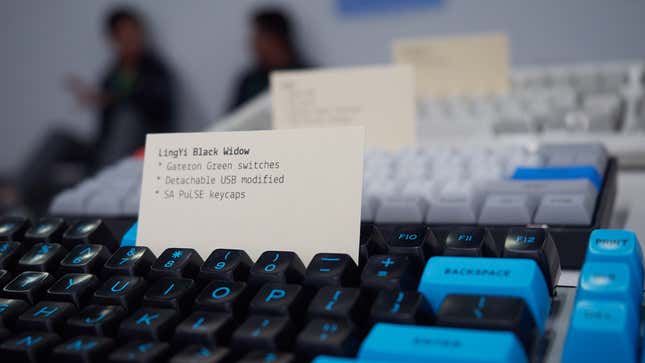

Most of these people (primarily men) have been talking on Reddit, Deskthority, geekhack, and Discord servers for years. They communicate in brands that the rest of us have never heard of, and over time, cliques have formed. While the bulk of the keyboards are mechanical, with big springs built into each key, there’s a handful of membranes in the group, which use the spongier mechanism similar to what’s in that old Dell keyboard you haven’t touched in years.

At a far corner, there’s a kid with a keyboard you can get at Best Buy. He’s lurking near a group of older father and grandfatherly sorts who’ve been collecting keyboards for ages. One, a Facebook engineer, actually built his own Bluetooth mechanical keyboard because he thought the wireless mechanical keyboard market was full of junk.

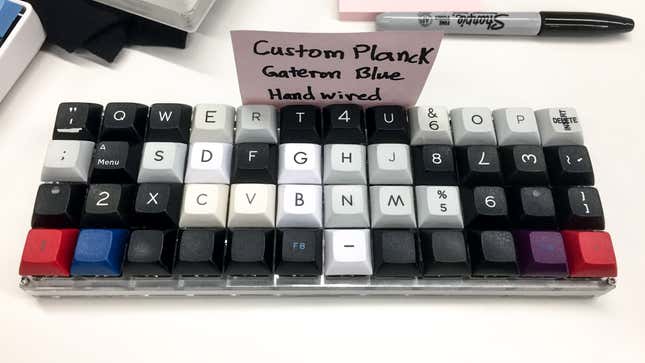

Closer to the snacks table sit some younger Facebook staffers. One of them has a Planck keyboard—a popular keyboard you have to build yourself, soldering switches to the circuit board (PCB) by hand. He even programmed his to make loud video game-like beeps—largely to annoy his co-workers.

But one table is swamped with keyboard fans from every clique. I give it a wide berth as I take in custom-built boards and others imported from overseas, but everyone I speak to nods in the direction of that table. “Have you talked to Jacob?”

“No,” I tell them, citing the big crowd. But I’m going to talk with him. Jacob Alexander is the man I’ve flown across the continent to meet. In the world of keyboards fans, Alexander, known as Haata on message boards, is king, a community legend online and off. He’s one of the leaders of a new breed of innovators hoping to revolutionize typing.

At first, it seems like a ridiculous ambition. Despite the troves of expertise of the men and women of the keyboard fan community, they’re still just expanding on a system so solid it hasn’t changed in 144 years. We’ve been clicking and clacking on some kind of keyboard since the Sholes and Glidden Type-Writer launched in 1873, and the design of keyboards has become fairly consistent. Rare alternative designs like the early Hansen Writing Ball (1870), the Maltron ergonomic line (1977) or the custom Planck board (2015) are outliers. Yet, that hasn’t dissuaded Jacob Alexander. He genuinely thinks there’s more to be done with the primary input device for our computers.

After the four-hour meet up, Alexander carefully wraps up the keyboards he’s brought—ones he designed with his partners at the small startup Input Club. The star of the show was the K-Type, an all white board with a multicolor LED around the base and brightly lit key caps, but some fans still eyed the older White Fox, which launched in December 2015 and lacks all the potentially garish lights.

Started by Alexander and crew in 2014, Input Club and its hugely anticipated keyboards sit at the core of this new fad that’s spreading rapidly online. Keyboard fandom’s Reddit boasts close to 200,000 members, and the community as a whole is large enough to support entire companies, like keycap makers Signature Plastics, and keyboard importer Mechanical Keyboards Catalog. For now, Alexander and the other four members of Input Club treat keyboard making as a passion project, and sustain themselves with regular day jobs. At night they meet online to hash out their plans to build and sell new boards and capitalize on the success of their early hits, like the White Fox.

The White Fox regularly appears on MassDrop, a popular website that organizes discounted group buys of products directly with manufacturers. The White Fox sells around 2,000 units each time it goes up for sale, and then goes for a premium on eBay or the MechMarket Reddit. When it isn’t available on MassDrop, you can expect to spend between $200 and $300 on a pre-assembled White Fox. For perspective, a mechanical keyboard from Logitech starts as low as $80.

The newest board from Input Club is the K-Type, which launched last Tuesday on MassDrop. It’s a “tenkeyless” keyboard, meaning the number pad has been chopped off to give it a smaller footprint. It’s easily one of the best feeling keyboards I’ve typed on, with a solid aluminum base that has a multicolored LED running around its edge, and some of the brightest lights I’ve ever seen on a keyboard.

Most members of the keyboard fandom tend to turn up their nose at keyboards with bright lights, perceiving them as a fad of less enthusiastic gamer sorts, but the K-Type already has a cult following on the message boards with thousands ready to drop $200 on the board, sight unseen. No one can tell me precisely why they like it versus a similarly garish keyboard from Razer or Logitech. Except Alexander.

As he follows me to my rental car, Alexander extols the virtues of the K-Type. “It’s not perfect, but it’s closer to what I envision you can do with keyboards,” he says. He notes how all its custom settings are stored on the keyboard itself. Want to move the Escape key to the Tab key, or change the Caps Lock to a Shift? Or maybe you’re finally ready to move from the common QWERTY layout to the hipster Colemak, which completely rearranges the order of the keys to put the most frequently used keys under the strongest fingers. It’s merely a matter of using Input Club’s open source firmware to change things around. Once its installed on the keyboard, there’s no extra software to load onto a computer, which means it remembers settings from computer to computer. It’s a minor thing for most people, but for his legions of fans, it’s a big deal.

By the time we get to the car, the rain that’s been steadily drumming all day tapered off to a fine mist. It fogs Jacob’s glasses and clings to his sandy blond hair. He’s a tall guy, lanky like a basketball player, with a goofy smile that you can’t help but find charming.

And he never stops being enthusiastic. He’s been on his feet for more than four hours, but as we make the forty-five minute drive from Menlo Park to his lab in downtown San Jose he doesn’t stop talking. He hast big dreams and he’s happy to share them, confessing that he joined Input Club, and built his keyboard lab because perhaps more than anyone else at the Facebook meetup, he “wants to change the way we type.”

He can’t exactly give me a major pipe dream he’s aiming for, though. There’s no far-flung futuristic idea he’s willing to share with me. Instead, he’s about refining and improving the keyboards we currently have. Most of us are on laptops with keyboards that use a nice enough scissor switch, or we’re on a mushy membrane-based keyboard issued by our offices along with our computers. The truly unlucky are typing on the glass surface of a tablet or using a terrible iPad keyboard. Alexander thinks we can all have a better experience.

While the keyboard seems simple enough, there’s a lot going on inside that changes dynamics of how we type. There are obvious factors, like the kind of switch, the shape of the keycap, or the layout of the board. Yet there’s also the input: Bluetooth or USB-C or plain old USB 3.0. Or the software, which might let you program which keys deliver which input or which key lights up with which color. There’s even the PCB board: The circuit board the switches are attached to.

Jacob and his colleagues at Input Club, like the rest of the keyboard community, have a fascination with all those components. And Jacob tells me, on our drive back to San Jose, that he doesn’t feel like all those little pieces have enough attention paid to them by the big guys. That’s why he wants to “disrupt” the keyboard world and forge innovations that cause the big guys, like Razer and Logitech, to notice. Which is doable. One Logitech rep we spoke to was aware of the White Fox, and both Razer and Logitech admitted to Gizmodo they watch out for small run products that get a lot of buzz.

Alexander talks like the technological giants Silicon Valley has since deified. Yet he’s not one of those polished next-gen nerds populating the countless investment firms we motor by on the 101. He is unmistakably a geek.

And if you somehow miss that fact when you attend a Bay Area keyboard meetup, it’s immediately apparent when you walk into his lab, which is situated on the top floor of one of the oldest and tallest buildings in San Jose. I watch the sun set from my gorgeous vantage point as he carefully unpacks his keyboards and returns them to his collection of over 500 others.

Alexander has been collecting for over ten years now. What first started as a hobby while he was in school in Japan, has transformed into a full-on lab.

The lab is separated into three big parts. One is a lounge area used primarily by the owner of the space. It reminds you of the office of any ill-advised startup. There’s a big TV and a billiards table, and that stunning view of the city. Jacob spends his time in the other two halves of the space. On one side, there’s a table piled high with keyboards dating back to the ‘60s and from places as far away as Russia. Behind them are a series of bookcases. Each holds dozens of meticulously labeled white boxes filled with keyboards.

The other half of the space resembles a traditional lab. There’s a station for checking the voltage on keyboards and their input and output signals. Another large desk is covered in a half-dozen soldering irons.

The most important part of Jacob’s lab is the part that’s easiest to miss. Every keyboard fan has one component they love more than any other. “I’m a switch person,” Jacob said. He’s fascinated with the mechanism you press to register an input on the computing device. Switches range from the membrane kind found attached to your old Gateway desktop, to the scissor switches in your laptop, to the mechanical ones most modern keyboard enthusiasts enjoy.

And every mechanical switch is different. Personally, I’ve got three types at my desk—the popular Cherry Brown you might find in an ultra fancy gaming laptop, old ALPs popularized by Apple’s mechanical keyboard, and newer Topres, which are a hybrid between mechanical and membrane boards.

Cherry was founded in 1953 and has making mechanical switches since 1984. It’s by far the most popular maker of mechanical key switches and the company has inspired a lot of “clones” like Gateron, Kaihua, and Zealio. It’s these clones that Jacob’s especially interested in. Despite appearing the same from the outside, each switch has a different “feel.”

Traditionally the feel is characterized by noting the distance it takes a key to “bottom out” on a board and the amount of force it takes to press the key. But Jacob wanted to go further. He understood that the force it takes to press a key is not constant, and instead a curve. There was no machine available to consumers or eager startups to measure such a force curve.

So Jacob built his own. He acquired a force gauge that you can get at any machinist supply store and bolted it to a robot connected to his computer. Since building the rig, Jacob has measured hundreds of keys. That includes every switch in the keyboards in his lab, plus many others manufactured primarily for do-it-yourselfers building their keyboards from scratch. He does it with practiced ease, and he guides me through the process, which can take upwards of ten minutes for a single switch. It requires a lot of complicated coding he does on the fly in a terminal window on his Linux-based desktop.

Nearly every night, when most of us would be turning our brains off after working all day, Jacob makes the trek to his lab, gathers a handful of keys, and tests them, often staying until eleven or later. “I can get through thirty in a night,” he admits.

When his Input Club colleague Andrew Lekashman told me about the tester, he pitched it as part of Input Club’s devotion to building a perfect keyboard and deciding precisely which switch they’ll install on their next board. But Alexander’s private goals are a little more lofty. “Keyboards were just neglected since the ‘80s,” He said, “I’m trying to help, with the rest of the keyboard community, to just push them forward.”

Alexander and his friends in the Input Club aren’t the only hobbyists with an eye on innovating their ways into a day job. The keyboard community is growing. One hub of the community, r/MechanicalKeyboards on reddit, gains more than 1,000 new followers every week. The industry supported by these fans is growing too.

At the Facebook meetup, Jesse Vincent set up shop with his enormous Keyboardio Model 01. After Jacob he’s the man people in the know encourage me to see. His partner, Kaia Dekker, is absent, but Jesse’s energetic enough to power through the four hour session despite frequent questions about the eta on his crazy looking ergonomic keyboard.

This blend of wood and machine began life as a hobby in 2012, before transforming into a Kickstarter in 2015 that earned over $650,o00. Since then, the project has been met with countless delays, often involving the manufacturing process—a common problem for new entrepreneurs on crowdfunding sites. Vincent sighs every time someone asks when the Model 01 is finally coming. He’s been dealing with backers for two years now. The first iteration, he tells the curious—voice tinged with the desperation of any successful crowdfunder struggling to deliver—should ship by the fall of 2017.

Henry Liu and his small team at Zeal PC have developed a cult following among keyboard enthusiasts too, and unlike Keyboardio, they haven’t had many difficulties with manufacturing. Avoiding crowdfunding, and the hazards of going it alone, Zeal PC partnered with Gateron in 2015 to craft Liu’s super popular Zealio switches. Fans will happily spend a $1 per key switch. That’s over $60 dollars just for switches—not including the PCB, case, key caps, or labor required to turn those key switches into a full board.

Liu (who goes by Zeal on forums) says the business is lucrative enough that it supports him and another staff member full time. “It’s pretty much the main job,” he told Gizmodo.

Jacob Alexander is a fan of Liu’s work, particularly with Gateron. “He whipped them into shape.”

The key to Liu’s success is his attention to detail when crafting the Zealio switch. It started as a mod of the popular Cherry Clear switch. “They bottomed out at like 100 grams,” he said, immediately shifting in the lingo of keyboard fans. Clears should bottom out at closer to 60g, which would mean it would take less force for the user to have the key hit the keyboard plate underneath. Liu’s original business, in 2014, was meticulously modding individual switches and replacing the springs in each by hand.

Then Liu made a deal with Gateron, known for its popular Cherry switch clones, and began producing his own Zealio switches. The key difference in his switches versus a similar switch from Cherry was in the molding process. “I wasn’t satisfied with how scratchy [Cherry switches] felt,” he said. According to Liu, Cherry has not properly maintained the molds the switches are made in. “It looks like sandpaper,” he said. That leads to friction as you press the key down. Which, in turn, leads to the scratchy sensation Liu and other fans felt.

The difference between his switches and Cherry’s are so readily apparent to the fans that they’ll happily spend sixty to a hundred dollars on switches alone, just to solder them into a PCB themselves. And that eager market of fans willing to spend wads of cash has allowed him to pursue other cool projects under the Zeal brand, like the Zeal 60 PCB.

PCB is the circuit board the the switches are soldered into—in essence, it is the heart of a keyboard. Liu proudly notes his is the first open source PCB with full RGB customization. If you solder on switches and LEDs yourself you’ll have a board any gamer would enjoy. Which means you can finely tune any key on the board to a specific glow.

If that keyboard, once built, sounds awfully similar to the aforementioned K-Type from Alexander’s Input Club than you’d be correct. But, “we were the first,” Liu noted. “K-Type’s the first fully assembled.” Right now anyone can pre-order Liu’s PCB board and build their own hyper-customizable keyboard, but Input Club’s K-Type will be the first that comes entirely pre-assembled. No soldering iron, or extra money for switches, just a good clean keyboard.

And if you think there’d be some serious competition between the titans of typing you’d be wrong. “I don’t have a bad thing to say about those guys,” Liu said with a chuckle. “I think what they’re doing is great. Everything’s open source. Once the board is out they’re they’re willing to show they’re designs. They’re really innovating.”

Henry Liu points largely to Input Club’s willingness to make everything open source as the reason the company is considered so innovative in the community. With the K-Type, if you don’t like something about it, you can tweak it. You can solder your own board from their specs or change out key switches or fundamentally alter the software. Provided you have the time and technological know-how, you can mod a K-Type to your heart’s content or create a whole new keyboard based on its schematics.

The willingness to do whatever it takes to make the community happy and get as niche as possible is a big reason why Input Club, and Zeal PC have the following they do. These companies are driven by their passion. It’s fine if their profit margins are low. Zeal PC supports two staff members full time, while most of Input Club has second jobs. They’re small enough that they can take risks like building super customizable open source $200 keyboards.

That flexibility is something larger keyboard companies don’t have. Logitech, with over $2.21 billion in sales, is one of the largest computer peripheral companies in the world. Unlike many of its competitors in the keyboard game, it’s also publicly traded, which severely limits the kind of daring products it can produce, as it has a duty not just to fans, but to shareholders.

“We can’t take the burden of risk,” Andrew Coonrad, a Technical Marketing Manager at Logitech explained. “But if there are those people who are pioneers—all industries rely on people like that to cut through with new and interesting stuff and if it does become super popular and people demand that sort of thing than certainly we’re gonna want to involve that design philosophy in our products.”

That doesn’t mean Logitech doesn’t experiment—its mechanical Romer-G switches have a small following in the keyboard community because the LEDs under the switches appear especially vibrant, and its new key caps are unique enough to be extremely divisive in the community.

In fact, Logitech insists it’s every bit as obsessive with finding the perfect key switch as Alexander. Its representatives balked when I told them that Jacob Alexander claims there hasn’t been a genuine study into typing efficiency and ergonomics since the 1960s. “There has,” the Coonrad told Gizmodo. “We just don’t share our findings.”

Kushal Tandon, the keyboard Project Manager at Razer was also quick to defend the big guys, in an e-mailed statement to Gizmodo. “We work with the singular focus of delivering the best product for professional gaming and esports athletes, and that is why we developed our own mechanical switch back in 2014.”

Razer’s switches, in fact, strongly resemble Cherry ones, though, like Zeal’s switches they definitely feel “smoother.”

But nothing Razer or Logitech makes will have the high actuation requirements of the switches made by Zeal or Input Club. The men behind those companies love key switches that require a lot of force to type on, forcing fingers to recollect the days of hurried papers on a Selectric typewriter. Logitech’s output demands a much lighter touch that the company feels has broader appeal in the market.

Perhaps that’s what’s keeping the K-Type from sitting on a shelf at Best Buy next to a Chroma or Romer-G based keyboard. Some people use smartphones as their primary computer, and others use the new MacBook Pro with its notoriously shallow keys. People simply haven’t experienced a more satisfying clack.

Alexander thinks that’s the case. “Everyone has to type,” he said with an eager chuckle. He just wants to make sure that what you’re typing on is the best. Even with his giant machine and hundreds of hours of research, he insists there isn’t a magic formula to that perfection yet. “There’s no best keyboard... There’s the best keyboard for you. ”