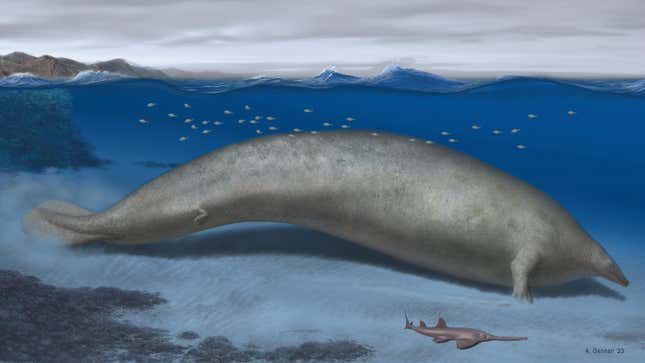

A team of paleontologists has announced the discovery of an Eocene-era whale it believes may be the heaviest animal to ever live, surpassing the extant blue whale in mass.

The behemoth is named Perucetus colossus, its genus name being derived from its country of origin. The animal’s fossilized remains were found in Peru’s Pisco Basin, between the towns of Pisco and Nazca. It lived about 39 million years ago, based on biostratigraphy and dating of Argon in the layers at which the remains were found.

But here’s the crazy part: the titanic whale weighed anywhere between 93.7 and 374.8 tons (85 and 340 metric tons). In common internet parlance of the 2010s, one could consider the Eocene whale chonky, perhaps the chonkiest creature of all time. To put it in perspective, at the upper bound of 374.8 tons, that’s roughly the same weight as 62 large elephants. The team’s research describing the superlatively sized species was published today in Nature.

“So far, extreme gigantism in cetaceans, as seen in the baleen whales, has been regarded as a relatively recent event (around 5 million years ago) and associated with offshore habits,” said Eli Amson, a paleontologist at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, in an email to Gizmodo. “Thanks to Perucetus, we now know that gigantic body masses [were] reached 30 million years before previously assumed, and in a coastal environment.” To which he added: “The discovery of the new fossil hence shows us that the coastal environment can sustain such a gigantic animal, something we did not expect at all.”

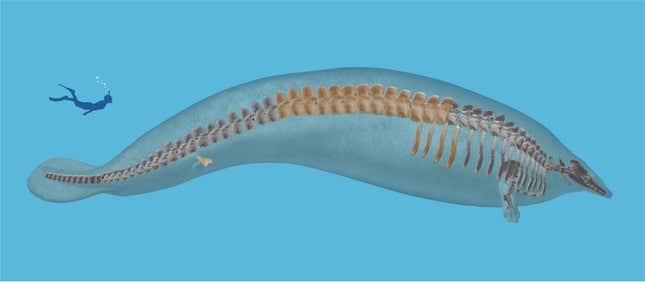

P. colossus—which translates to “colossal whale from Peru”—was first excavated in 2010 by paleontologist Mario Urbina, a co-author on the new study, in the Peruvian desert. The team required several field campaigns over the intervening years to dig out the 13 vertebrae, 4 ribs, and singular hip bone that comprise the specimen. The researchers also found intact vestigial hind limbs of the whale, harkening back to landlubbing and semi-aquatic whale ancestors like Pakicetus.

Though the research team was able to estimate the whale’s size from the partial evidence, they had to extrapolate a good deal regarding the animal’s mass and ecology. P. colossus had dense bones, which lack the spongy interior of many mammalian bones.

“What surprised us is that this adaptation could reach such a tremendous degree,” Amson said. “The vertebrae are so inflated due to additional deposition of bone tissue that it was even hard to recognise the diagnostic characters of the family.”

The research team determined that P. colossus was a basilosaurid, a member of the ancient whale family that existed across Earth’s oceans between the Eocene and Oligocene epochs. The most famous member of the family is arguably its namesake genus Basilosaurus, but the family includes other species like Dorudon atrox and Kekenodon. P. colossus’ dense bones led the researchers to conclude the animal was a shallow-water scavenger rather than a deep sea diver.

Hans Thewissen and David Waugh, mammalogists specializing in whales at Northeast Ohio Medical University, wrote a Perspectives article accompanying the new paper. “P. colossus is a major discovery but the limitations of the fossil should be acknowledged,” Thewissen and Waugh noted. “Many parts of the skeleton, such as the skull, for instance, remain undiscovered. We have few clues as to how old the individual was when it died and can only make inferences about its life history.”

The research team estimated P. colossus’ mass using the ratio of soft tissue to skeletal mass present in most mammals. Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are generally considered the most massive animal to ever grace the planet; the largest accurately measured specimen was about 200 tons (180 metric tons) but there are reports of some specimens weighing 220 tons (200 metric tons), according to Brittannica. The lower mass estimate for P. colossus puts it in the same ballpark as blue whales, but the upper mass range (375 tons, or 340 metric tons) would see it well out of the park and into a completely different sport.

Thewissen and Waugh state that the amount of dense bone in P. colossus’ body indicate the animal had a lot of low-density tissues (e.g., blubber) that increased its total weight. “If P. colossus had a life-history strategy similar to that of sei and bowhead whales, was this a young individual that carried copious and buoyant body fat, and its skeleton provided weight for ballast? Could this fossil be a testament to the origin of blubber? That hypothesis is consistent with the fossil’s age of around 39 million years old, from a time when Earth and the oceans were cooling and insulating blubber might have been an advantage,” the researchers added.

P. colossus shakes up scientists’ understanding of how big creatures can get, and when they did so in evolutionary history. Will things ever get that big again? Well, extant blue whales may still be the heavyweight champion. Besides, life (and thus, evolution) will go on when humankind is fading away in Earth’s rearview mirror. New shakeups, namely climate change, will likely have an impact on how animals adapt to new environments.

If paleontologists find more complete specimens of P. colossus they could better constrain the enormous mass range currently placed on the animal. The arc of the evolutionary universe is long, but as this new whale-of-a-find shows, it bends towards the imaginative.

More: Paleontologists Predict What Future Animals Might Look Like