Picture a cat. I’m assuming you’re imagining a live one. It doesn’t matter. You’re wrong either way—but you’re also right.

This is the premise of Erwin Schrödinger’s 1935 thought experiment to describe quantum states, and now, researchers have managed to create a fat (which is to say, massive) Schrödinger cat, testing the limits of the quantum world and where it gives way to classical physics.

Schrödinger’s experiment is thus: A cat is in a box with a poison that is released from its container if an atom of a radioactive substance, also in the box, decays. Because it is impossible to know whether or not the substance will decay in a given timeframe, the cat is both alive and dead until the box is opened and some objective truth is determined. (You can read more about the thought experiment here.)

In the same way, particles in quantum states (qubits, if they’re being used as bits in a quantum computer) are in a quantum superposition (which is to say, both “alive” and “dead”) until they’re measured, at which point the superposition breaks down. Unlike ordinary computer bits that hold a value of either 0 or 1, qubits can be both 0 and 1 simultaneously.

Now, researchers made a Schrödinger’s cat that’s much heavier than those previously created, testing the muddy waters where the world of quantum mechanics gives way to the classical physics of the familiar macroscopic world. Their research is published this week in the journal Science.

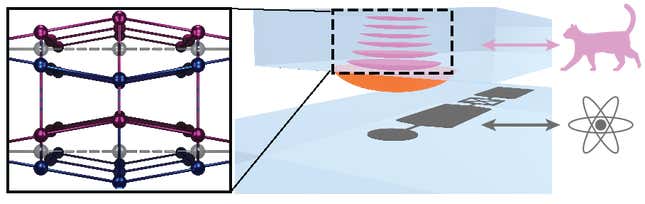

In the place of the hypothetical cat was a small crystal, put in a superposition of two oscillation states. The oscillation states (up or down) are equivalent to alive or dead in Schrödinger’s thought experiment. A superconducting circuit, effectively a qubit, was used to represent the atom. The team coupled electric-field creating material to the circuit, allowing its superposition to transfer over to the crystal. Capiche?

“By putting the two oscillation states of the crystal in a superposition, we have effectively created a Schrödinger cat weighing 16 micrograms,” said Yiwen Chu, a physicist at ETH Zurich and the study’s lead author, in a university release.

16 micrograms is roughly equivalent to the mass of a grain of sand, and that’s a very fat cat on a quantum level. It’s “several billion times heavier than an atom or molecule, making it the fattest quantum cat to date,” according to the release.

It’s not the first time physicists have tested whether quantum behaviors can be observed in classical objects. Last year, a different team declared they had quantum-entangled a tardigrade, though a number of physicists told Gizmodo that claim was poppycock.

This is slightly different, as the recent team was just testing the mass of an object in a quantum state, not the possibility of entangling a living thing. While that’s not in the team’s plans, working with even larger masses “will allow us to better understand the reason behind the disappearance of quantum effects in the macroscopic world of real cats,” Chu said.

As for the true boundary between the two worlds? “No one knows,” wrote Matteo Fadel, a physicist at ETH Zurich and a co-author of the paper, in an email to Gizmodo. “That’s the interesting thing, and the reason why demonstrating quantum effects in systems of increasing mass is so groundbreaking.”

The new research takes Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment and gives it some practical applications. Controlling quantum materials in superposition could be useful in a number of fields that require very precise measurements; for example, helping reduce noise in the interferometers that measure gravitational waves.

Fadel is currently studying “whether gravity plays a role in the decoherence of quantum states, namely if it is responsible for the quantum-to-classical transition as proposed a couple of decades ago by Penrose.” Gravity doesn’t seem to exist on the subatomic level and is not accounted for in the Standard Model of particle physics.

The quantum world is ripe for new discoveries, but alas, it’s crammed full of unknowables, dead ends, and vexing new problems.