A team of paleoanthropologists has assembled the only known cranium of the extinct ape Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, revealing how the ape’s face looked. The reconstruction allows them to place Pierolapithecus on the hominid family tree and improves our understanding of how the ape moved around Spain some 12 million years ago.

Pierolapithecus was first described in 2004, when a partial skeletal and facial cranium were found in a landfill on the outskirts of Barcelona, Spain. The specimen dated to over 12 million years old and was found alongside two other genera of extinct ape: Dryopithecus and Anoiapithecus. By the original team’s assessment—based on Pierolapithecus’ “primitive monkeylike” characteristics and its skeleton, which indicated the ape could take on an upright posture—the specimen was closely related to the last common ancestor of great apes and humans.

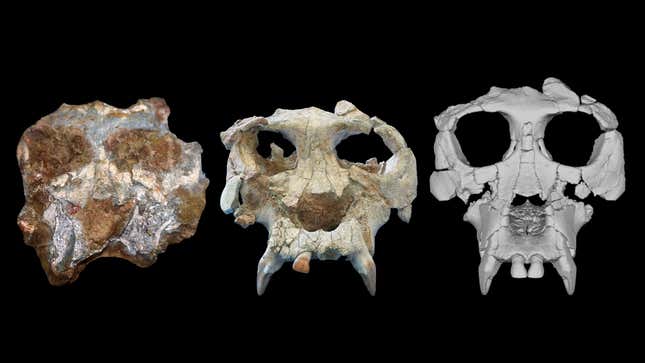

In the new research, the team CT-scanned the fossil cranium to virtually reconstruct it and better compare the specimen to other known hominids. The research is published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Features of the skull and teeth are extremely important in resolving the evolutionary relationships of fossil species,” said Kelsey Pugh, an anthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the study’s lead author, in a museum release. “When we find this material in association with bones of the rest of the skeleton, it gives us the opportunity to not only accurately place the species on the hominid family tree, but also to learn more about the biology of the animal in terms of, for example, how it was moving around its environment.”

An ability to take on an upright posture suggests that Pierolapithecus, like many other hominids, could hang on branches and navigate through the canopies. That was previously known, but the condition of the fossilized cranium made it hard to understand where the ape was situated taxonomically. Once CT scans were made of the cranium and it was virtually pieced together, the researchers were able to compare Pierolapithecus to other known hominids.

“One of the persistent issues in studies of ape and human evolution is that the fossil record is fragmentary, and many specimens are incompletely preserved and distorted,” said study co-author Ashley Hammond, a biological anthropologist at American Museum of Natural History, in a museum release. This makes it difficult to reach a consensus on the evolutionary relationships of key fossil apes that are essential to understanding ape and human evolution.”

The team found that Pierolapithecus’ had similarities with those other great apes extinct and extant, in terms of its general shape and size. Based on evolutionary modeling featuring the newly measured characteristics of the Pierolapithecus cranium, the team determined some facial aspects of last common ancestor of hominids. That ancestor, the team wrote “was distinct in overall shape from all extant and fossil hominids and similar in many features to Pierolapithecus.”

Our last common ancestor remains elusive, but aspects of it are slowly becoming more resolved thanks to newly found fossils and new ways of interrogating previously discovered ones. The newly CT-scanned cranium is allowing scientists to look into the face—almost—of this enigmatic member of our family tree.