Paleontologists have found a fossilized pterosaur precursor with gnarly, scimitar-like claws and a beak, indicating that the reptilian group it belongs to was more diverse than previously thought.

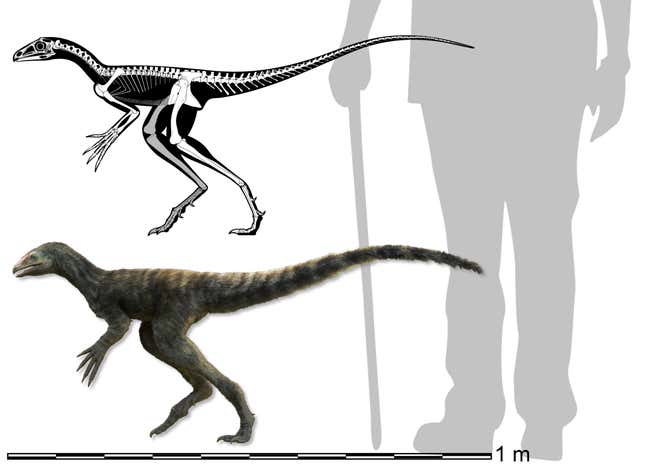

The species—dubbed Venetoraptor gassenae—is a lagerpetid, a group of reptiles that lived during the Triassic period. Lagerpetids belong to a different branch of life’s tree than dinosaurs; they likely gave way to pterosaurs, the earliest vertebrates to develop powered flight. A new paper describing the curious morphology of V. gassenae was published today in Nature.

“Because cranial remains are so scarce for lagerpetids, this is the first reliable look into the face of these enigmatic reptiles,” said Rodrigo Müller, a paleontologist at the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria and the study’s lead author, in an email to Gizmodo. “The unusual skeleton of Venetoraptor gassenae reveals a completely new morphotype of pterosaur precursors.”

Müller discovered the species holotype in 2022, in southern Brazil’s Santa Maria Formation. The specimen dates to the Late Triassic period, about 230 million years ago. Müller said he knew it was a lagerpetid based on the look of the specimen’s femur. “The skull and hand were revealed after the laboratory preparation of the specimen,” he added. “At this point, this specimen became the most informative lagerpetid ever found.”

Lagerpetids existed over 200 million years ago; as previously reported by Gizmodo, their claws were likely used for actions beyond locomotion, like climbing and hunting.

In 2021, a different team of paleontologists discovered K. antipollicatus, or the opposably-thumbed ‘Monkeydactyl’, a Darwinopteran pterosaur that hints at the evolutionary shift from lagerpetids to pterosaurs. Pterosaurs died out alongside the dinosaurs in the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction about 66 million years ago.

The recent team posits that V. gassenae’s slender (or “scythe-like,” per the paper) claws were probably used for those familiar reasons for lagerpetids: to catch prey or climb. It confirms that at least some lagerpetid lineages lost quadrupedalism, or at least preferred to move on two legs.

But the animal’s beak is a more open-ended matter—besides feeding, beaks can have utility in animal vocalization, temperature regulation, and sexual displays. The raptor-like beak on the species precedes the same feature among dinosaurs by about 80 million years. “The ecological role and evolutionary advantage of such a beak in Venetoraptor are uncertain,” the team wrote, but the beak’s presence (the first evidence in the clade) “ expands the morphological spectrum of beaks within Pterosauromorpha.”

Lagerpetids may yet yield more of their secrets, indicating how the enigmatic group of reptiles gave way to flying descendents, including the largest known animal ever capable of flight, Queztalcoatlus.

“The next steps include non-invasive techniques such as computational tomography in order to reconstruct the brain endocast and hidden structures,” Müller said.

As is always the case in paleontology, more specimens never hurt. So hopefully southern Brazil offers up a trove of Triassic creatures in the near future—some of these fossils have been waiting 230 million years to be found.