A few weeks ago, my editor asked me to review a new telescope. Having never reviewed a single product for Gizmodo in all the years I’ve worked here, and having never laid my hands on a telescope, I made a valiant attempt to weasel my way out of this assignment. Unswayed by my arguments, my editor described the telescope as being “idiot-proof,” and as such, that made me a perfect candidate to review the new product. Hmph.

Having no choice but to acquiesce, I agreed to give Vespera a go. As an absolute beginner to backyard astronomy, I was certainly intimidated by the $2,499 price tag, but I found the experience to be anything but. This mechanized telescope is a cinch to use and a fantastic introduction to astrophotography. In short order, I went from not wanting anything to do with this telescope to not wanting to send it back.

Believing that two idiots are better than one, I recruited my young adult son, Calvin, to help with the “observation station,” as Vaonis, the France-based manufacturer of Vespera, refers to the device. Unboxing was a breeze, and within minutes, we had the hardware set up. Its 11 pound weight and 15 x 8 x 3.5 inch body makes it manageable enough to carry around (Vaonis even sent me a Vespera-specific backpack, which can be purchased separately). All we needed to do was to screw in Vespera’s three legs, use the included bubble level to align it horizontally, and get it charging with a USB plug. It’s also IP43 water resistant, which protects it against splashes in case of rain.

The software component was also simple, only requiring us to download the company’s Singularity app onto a mobile phone. Not wanting to view the majesty of the cosmos on my iPhone’s tiny screen, I used an old iPad, and it worked just fine.

Indeed, this was the first “adjustment” that Calvin and I had to make—the realization that we weren’t going to make our celestial observations by peering directly through an eyepiece. With the backpack-sized Vespera, the experience was going to be digital and not analog, but that limitation didn’t bother us one bit. The acquisition of digital images, which we could easily share with friends and family (I literally air-dropped images to my wife while long-exposures were still taking place), or add to my (now) growing catalog of astronomical images, was ultimately where I wanted to go with all of this. Vespera, as we quickly learned, is essentially a mechanized camera that thinks it’s a telescope, and a good one at that.

Once we connected Vespera to my iPad via wifi, we were up and running. Vespera doesn’t come with an instruction manual, but a brief online tutorial and the associated Singularity app were pretty much all that we needed to get started. The device features a single, glowing button and an arm that extends automatically when it’s time to make observations. Battery life is listed at four hours, but this can be extended with a power bank.

Once it got dark outside, Calvin and I plopped the 11-pound (5-kilogram) device onto the ground, re-adjusted the leveling, and allowed the unit to orient itself through its automated initialization routine. The entire setup—from unboxing through to keying in the first target—took us maybe 20 minutes, which greatly exceeded my expectations.

A full Moon happened to grace the skies that night, making it a logical first target. Using the app, I chose the Moon from a list of target options, sending Vespera into action. A glorious image of the full Moon suddenly appeared on my screen, in more detail than any astronomical photos I had ever attempted before. It was instantly the best photo of the Moon I had ever taken—even if that photo was produced with the assistance of a robot. Cal and I then turned our attention to the planets, namely Saturn and Jupiter, but the resulting images were underwhelming, showing only tiny dots set against a starry landscape. To be fair, I was able to discern a ring-like feature around Saturn, but nothing beyond that.

It wasn’t until we began to image “invisible” objects like galaxies, clusters, and nebulae that the true power of Vespera came into focus. That’s because Vespera is primarily meant for deep-sky object photography. For solar system objects and visible stars, Vespera captures single-shot photos, but for celestial objects that can’t be seen with the unaided eye, the telescope runs long exposures, stacking the images to bring out details that are normally hidden. Vespera’s low light Sony sensor, 2-inch (50 mm) aperture, 8-inch (200 mm) focal length, and 1.6 degree x 0.9 degree field of view produced clear and crisp color photos, which we were able to save and share as high-res images.

You also get a decent amount of customization over these long-exposure shots, as a camera button pops up on the screen while you’re gathering light, letting you grab images at any point during the process. You can also easily toggle long exposure on and off with a simple “record” button, so you don’t expose your shot for longer than you want.

Images save to the telescope’s 11 GB hard drive by default, but you can also save them to your phone’s photo library. Resolution is a simple 1920 x 1080, and you can save in jpg, tiff, or fits format. It didn’t take long for us to gather some really neat photos. Over the course of the next several nights, Calvin and I captured images of the Cigar Galaxy, the Cat’s Eye Nebula, the Fireworks Galaxy, the Dumbbell Nebula (a personal favorite, as the colors really popped in our image), and the Pinwheel galaxy. The long-exposures took between 20 and 60 minutes, depending on the app’s recommendation, but the length of each exposure was largely up to us. One thing I really enjoyed was slowly watching an object come into focus over the course of the long exposure, and comparing the early image to the fully stacked end product.

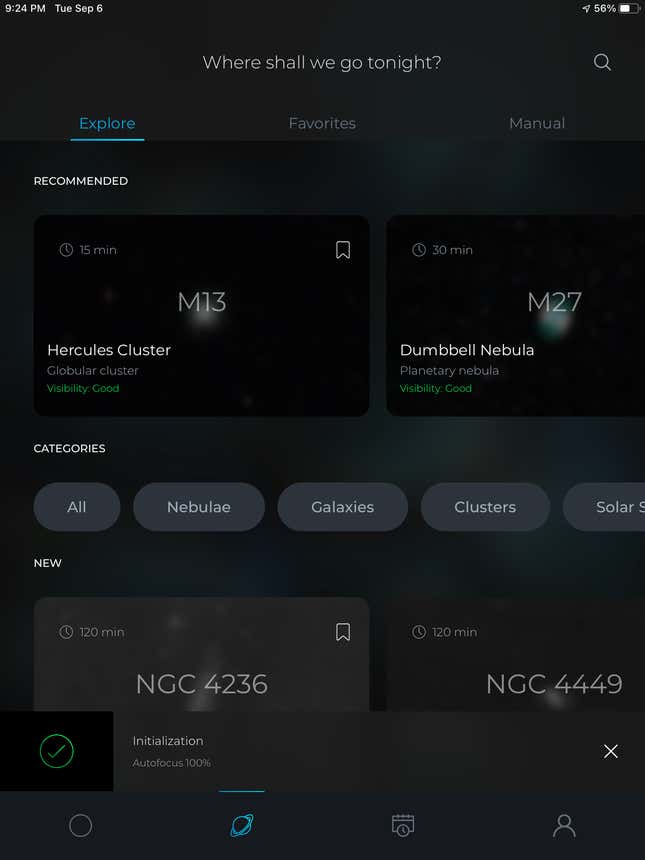

The mobile app, which lists over 250 objects in its preset catalog, offered information about each target object while we waited. The app also made viewing recommendations based on our geographical location and the current astronomical calendar. The Singularity app was approachable, but I also had fun choosing my own targets, which I often did using the Sky Guide app on my phone and then searching for the object in the Singularity catalog.

A concern I had going into the review was the intense amount of light pollution near my home. I live in the greater Toronto area, where dark skies are tough to come by. Vespera performed exceptionally well despite this, acquiring clear and crisp images even with the incessant ambient light. I can only imagine how well the telescope performs in darker areas. Vaonis does offer a $199 light pollution filter for the telescope, but I honestly didn’t really feel the need to use it.

With Vespera, Calvin and I suddenly fancied ourselves as astronomers, and the skies above us took on a new meaning as we investigated that which couldn’t be seen with the naked eye. I very much enjoyed the automatic, no-fuss nature of the experience, but Calvin was less impressed, saying Vespera felt more like a “toy” than a scientific instrument. For Calvin, the super-autonomous nature of the device and the extreme level of hand-holding were a bit much. But that’s precisely why I loved it. To be fair, however, the Singularity app does make it possible to go rogue, so to speak, as it allows users to manually explore targets by keying in user-defined coordinates.

And at the listed retail price of $2,499, Vespera is most certainly not a toy. The price tag may seem steep, but it’s the most affordable of Vaonis’s offerings, with the Stellina automatic telescope (released in 2018) retailing for $3,999 and the upcoming Hyperia telescope starting at $45,000 (yes, really).

This unit makes the process of acquiring long exposures a dream, as Vespera takes care of the focusing while automatically tracking target objects as they slowly shift across the field of view. A word of caution, however: users need to manually save images during the long exposures, otherwise they’re gone forever (we learned this the hard way).

The system also makes it possible for multiple users to join in on the fun, with connected individuals being able to watch the incoming images on their respective handheld devices. Control of the 15-inch-tall (38-centimeter) telescope can also be relinquished with the click of a button. Calvin and I didn’t really need the multi-user mode, but this feature would be super helpful when using the telescope with a group, such as when camping or out at the cottage.

Conventional telescopes range in price from several hundred dollars through to around $1,600, making them considerably more affordable than Vespera. So yes, backyard astronomy is possible on a budget, but most of these telescopes lack the smart functionality offered by Vespera, including the long exposure capabilities, the ease of use, and the quick sharing of photos. That said, Unistellar does offer a smart telescope, albeit one even pricier than Vespera.

Vespera fundamentally changed the way I think about backyard photoastronomy. It never occurred to me that I’d someday be able to capture vivid images of nebulae and spiral galaxies, but this tool made it possible for me to do so—and without having to leave the bright city. Vespera also changed the way I look at space, and it continually left me wanting to explore more of the skies above. As someone who gets easily intimidated by telescopes, Vespera is exactly what I needed to get over the hump.