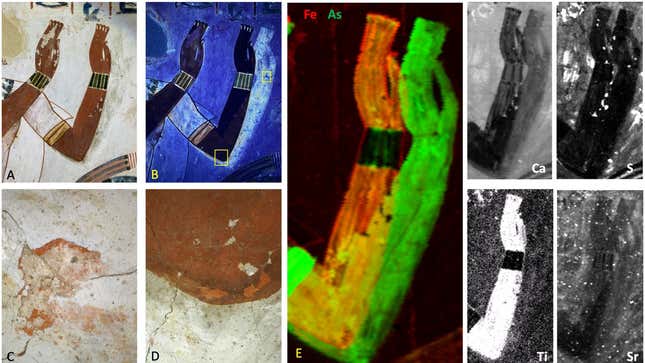

A team of researchers recently studied paintings in the Theban Necropolis near the Nile River using X-ray fluorescence imaging and discovered never-before-seen details of the painting process.

Under X-ray light, the 3,100-year-old paintings glowed with their artists’ first drafts, hidden to the naked eye for millennia. The team’s research was published this week in PLoS ONE.

“Documentation remains a problem in 2023 and thus what we are trying to do is basic documentation from different perspectives, using digital tools at different scales,” said Philippe Martinez, a researcher at the Sorbonne Université in Paris and the study’s lead author, in an email to Gizmodo. “For the first time, we can produce models that convey a real sense of space as well as high-res images that enable the viewer to see the reality of ancient paintings better than on site.”

To which he added: “Macrophotography, as well as different uses of X-Rays or multi- or hyperspectral imaging, enable us to really dig the painted surface at a molecular scale,” Martinez added.

The paintings are located in tomb chapels of the Theban Necropolis. They date to around the reign of Ramesses II (between 1330 B.C.E. and 1069 B.C.E.) The tomb chapels belong to Menna, an overseer under Amenhotep III, and Nakhtamun, chief of the funerary temple’s altar around the time of Ancient Egypt’s 20th Dynasty.

The Menna paintings are “universally known as the apogee of ancient Egyptian painting,” the researchers wrote, while “those of Nakhtamun remain underrated and simply inaccessible.”

In the new work, the researchers describe a third arm of Menna in one painting that shows up under ultraviolet light. The arm may have been removed for aesthetic reasons, as the team couldn’t figure an alternative reason, but they caution that we cannot know the aesthetic preferences of Ancient Egyptians.

The royal portrait of Ramesses II has its own curiosities. For one, the pharaoh is sporting a “budding beard,” a facial hair choice “rarely displayed in Egyptian art” and “even more for a king,” according to Martinez.

The Ramesses portrait also revealed an apparent shebyu necklace missing from the finished article. Shebyu necklaces are uncommon in depictions of Ramesses II.

Ancient Egyptian painting has been studied for centuries (if not millennia), but archaeological technologies have advanced considerably in the last several decades. Now, researchers can look at these ancient works and peel back the layers (of paint) noninvasively, and get remarkable looks at earlier drafts of artwork.

These revisions can reveal not just how artwork was produced in Ancient Egypt, but how the artists and the subjects of the paintings may have thought about religion and other cultural practices.

More: Ancient Egyptian Murals Show Lifelike Doves, Kingfishers, and Other Birds